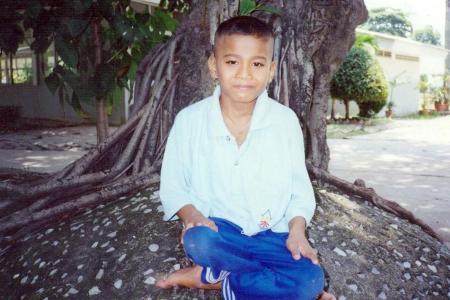

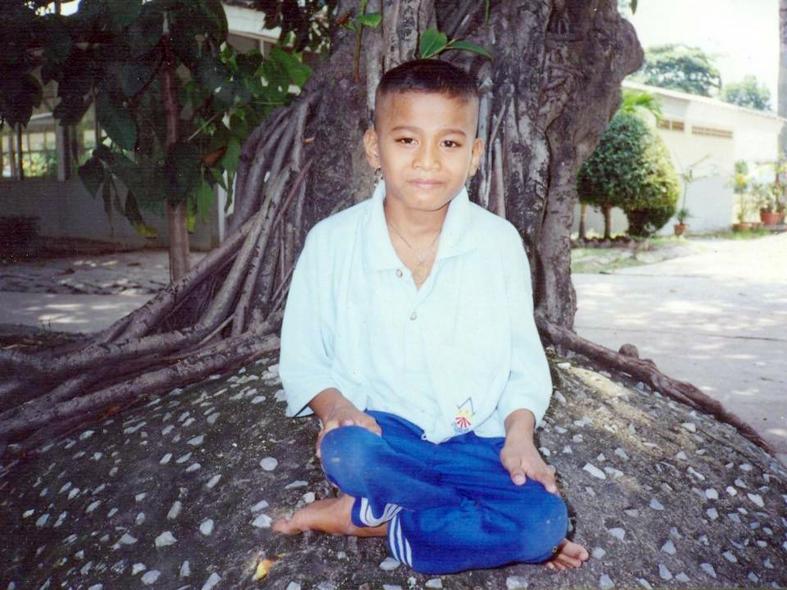

From beggar to undergrad – a human trafficking victim’s journey

When he was 6, Cambodian boy became a human trafficking victim, forced to beg in Thailand for six years

Your heart might have broken if you had seen Chhap Longdy when he was six.

He was diagnosed with polio when he was five and the Cambodian boy's legs were so skinny they looked as if they would buckle under his weight.

That same vulnerability made him a human trafficking victim for six years.

He spent those years begging in Thailand.

"We were really poor. We just got one meal a day," Mr Longdy, now 25, told The New Paper in halting English.

It was only with the intervention and help of non-profit anti-human trafficking groups like Hagar International that Mr Longdy is pursuing a psychology degree at the Royal University of Phnom Penh.

"My parents would tell everyone about it even though I got only a B for one of my subjects," the undergraduate said with a laugh.

Mr Longdy was in Singapore yesterday to be part of Hagar International's charity golf event, which raised $100,000 last night to help trafficked survivors.

The Singapore arm of Hagar International, Hagar Singapore, has been trying to raise awareness about human trafficking, said its executive director Michael Chiam. (See report on facing page.)

Mr Longdy's trafficking nightmare started with a broker who suggested that he beg in Thailand for a living. People would take pity on a child with a disability, the broker told the boy's mother.

She also promised that he would be fed properly and would live in a better house. Mr Longdy was six at the time.

"My mother talked to me about it. Initially, I was a little scared. The broker came to me and said I would be happy staying in Thailand. As a kid, the idea of going to Thailand was interesting. I thought it would help my family," he said.

It was a perilous three-day journey that saw him crawl through a forest at times before he crossed the border into Thailand.

Mr Longdy's hometown is in Banteay Meanchey, a province in Cambodia that shares an international border with Thailand.

But the real nightmare began when Mr Longdy started his "job".

"It was nothing like what the broker had promised," he said quietly. He cannot remember where he was taken to in Thailand.

On average, he collected 500 (S$20) to 600 baht daily, but only 30 per cent of what he collected was sent to his mother, he said.

When he collected less than usual, the broker would lay a guilt trip on him, reminding him of his family's dire financial situation.

He would also be given less food.

Every few weeks, to prevent him from getting help from locals and getting close to them, he was moved to a different house and made to beg at different locations.

The only time he returned home was when he was caught by the police and deported after spending two days in jail.

Although he was happy to be reunited with his family, he also felt guilty because he knew he was the family's breadwinner.

That guilt trapped Mr Longdy in the vicious circle. Each time he was approached by a broker to beg in Thailand, he would agree to it.

INTERVENTION

This went on for another six years before non-governmental organisations like the International Organization for Migration and Hagar Cambodia intervened.

Calling himself a "bad kid" who was rude and bad-tempered, he stopped bullying other children only when he saw the patience and effort put in by Hagar's case workers to change him.

Hagar Cambodia's counselling project manager Seng Mang said Mr Longdy's behaviour could be due to being exposed to "traumatic experiences" from young.

"At that age, most children are developing. So he probably remembered how he was treated, like being beaten up, and did that to others as well," he explained.

Through Hagar's economic empowerment programme, Mr Longdy's family is also earning enough to get by.

Said Mr Longdy with a smile: "They are not rich, but at least they now have three meals a day, with a snack in between. They have also stopped drinking and gambling."

He hopes to be the same inspiration to other victims by working for Hagar, where he is an intern counsellor.

"Another plan I have is to hopefully work with the United Nations," he added.

Wrong to withhold maid's passports

More needs to be done in raising awareness of human trafficking, said Hagar Singapore's executive director Michael Chiam.

"When you talk to your friends and families about human trafficking, they look at you with a blank face.

"Withholding the passports of domestic helpers, for instance, is an element of human trafficking and yet many employers do that," he pointed out.

Because of that, the non-governmental organisation (NGO) is working with voluntary welfare organisations here to see how they can raise awareness.

Last month, Hagar organised a workshop for NGO staff, volunteers and supporters on the new Prevention of Human Trafficking Act pushed forward by Member of Parliament Christopher de Souza.

Last August, Hagar conducted a training course for police officers on how to tackle the problem of human trafficking - how to ask the right questions, how to spot the victims and what to do if they suspect someone.

"One of the challenges is to find out who are the victims. Most of them come in legally, so you can't tell. Even when they go through the customs, they are taught exactly what to do and say," said Mr Chiam.

BY THE NUMBERS

In Singapore last year, there were:

228 human trafficking victims

49 trafficking cases involving labour exploitation

44 trafficking cases involving sexual exploitation

Figures from Trafficking in Persons Report 2014

Get The New Paper on your phone with the free TNP app. Download from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store now