A whole lot of croc in Kranji

This article was originally published on May 11 2014. At the time, crocodiles were reported at Kranji Reservoir and Sungei Buloh recently. But did you know there are at least 13,000 crocs in Kranji? Rei Kurohi visits the last surviving crocodile farm in Singapore

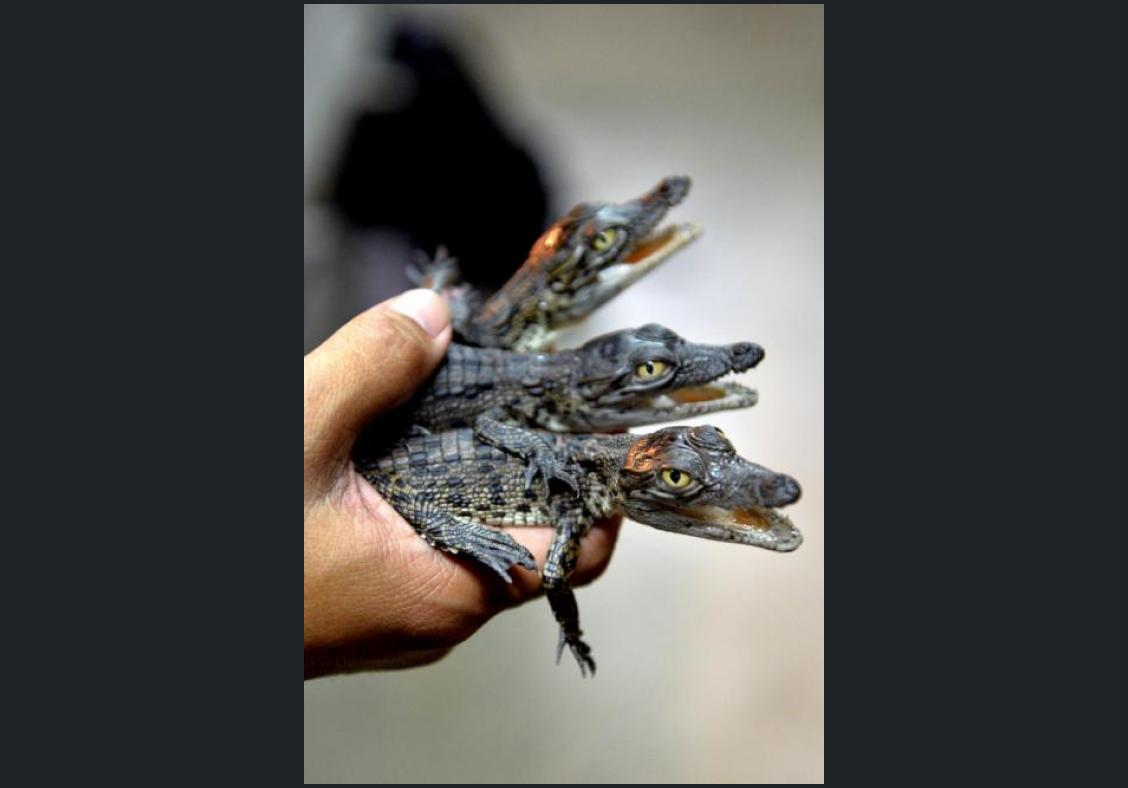

Chomp. The little week-old critter which bit this curious reporter’s finger was a mere 15cm in length.

It did not break skin but things would be different if it were one of the breeding adults at Long Kuan Hung Crocodile Farm in Kranji.

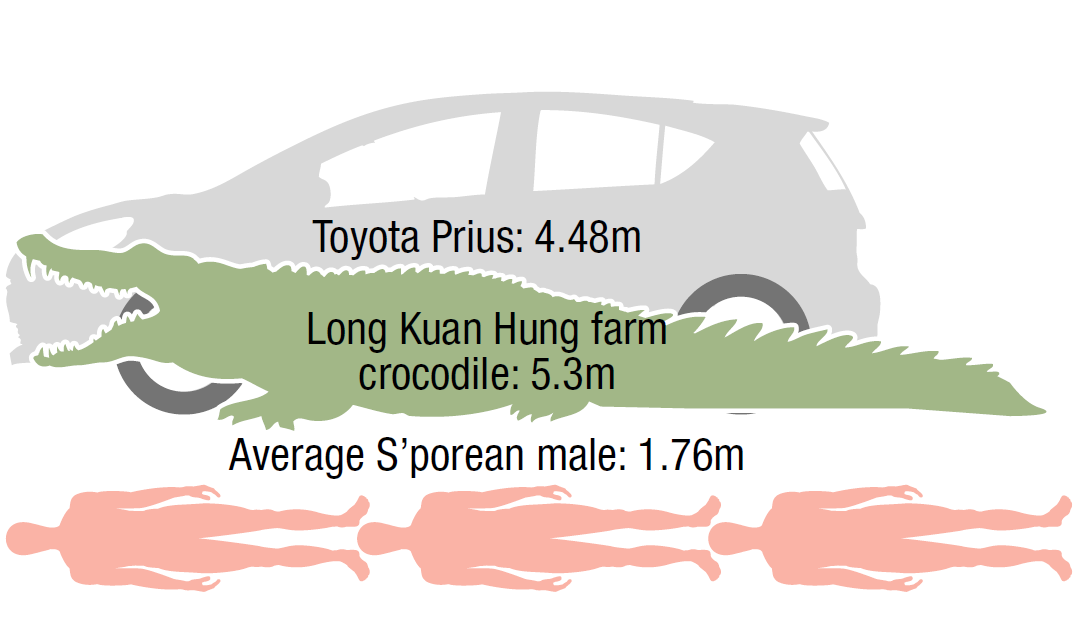

The largest male breeding crocodile in the three pens at the farm is about 5.3m (or 17ft). Indeed, this Singapore behemoth nears the record for the largest saltwater crocodile in captivity: A giant in the Philippines was reported at 20ft or 6.2m.

Though it has never been officially weighed, a crocodile of that size can easily exceed 600kg, dwarfing the 400kg Barney, which was found dead recently.

“The first thing I tell my staff when they join me is never to put their hands or heads into the enclosure,” says farm manager Robin Lee, 39.

“If you follow what I say, you can work for me for 20 years and I guarantee you won’t get hurt,” he adds.

He is quick to clarify that his farm did not receive Barney’s carcass, as netizens speculated. In fact, he did not even know about the dead crocodile until he read about it last Sunday.

On Thursday, The New Paper on Sunday asked PUB what had happened to the carcass but it did not reply by press time.

Previous reports state that there are believed to be 10 crocodiles in the waters of north-eastern Singapore.

But their fellow creatures in captivity at Singapore’s last remaining crocodile farm are closely monitored and ministered to by a team of about 20 people.

They oversee every aspect of the crocs’ lives. The reptiles’ eggs are carefully harvested from January to June each year and incubated for 82 days.

Out of over 3,000 saltwater crocodile hatchlings produced each year, a select number are kept for breeding. The rest are slaughtered when they are five years old for their meat and skins, yielding 1,600 skins annually.

The skins are exported mainly to Japan and Europe, while the meat is sold to local restaurants and supermarkets.

Mr Lee’s farm, which he inherited from his father, perpetually conducts research on how to increase the production of eggs and improve the welfare of his crocodiles.

“We ensure that they have sufficient space to grow. You have to keep them happy, so they don’t fight among themselves,” he explains.

Mr Lee is proud of the farm’s strict standards of safety and security.

Indeed, this reporter saw a mother crocodile aggressively protecting her nest.

When Mr Lee approaches, she clambers up a mound of dirt and snaps her jaws above the concrete walls of the breeding pen, making a sound like two bricks being slammed together.

But her short legs do not allow enough her enough purchase to get over the walls. Mr Lee and his workers ensure that none of their crocodiles have ever escaped.

“We monitor the pens daily. If a dirt mound goes beyond a certain height, we will level it,” he says.

Mr Lee’s passion for crocodiles is palpable. He even keeps a few of them as pets, including a 20kg “dwarf” saltie, named Baobei (“precious” in Chinese), which has its own special indoor enclosure.

Baobei will submit to being cradled and carried. But she had her jaws bound while our photographer snapped.

Mr Lee feeds his crocodiles chicken heads and necks thrice a week.

“Some of them are quite spoiled,” he says with a laugh. “Once they’ve had their fill, they would ignore the extra food. After a day or so, they won’t eat anymore until we flush out the extra food and give them fresh items.”

Business at the farm has been good. Even as other crocodile farms and attractions around the island have closed down over the years, Mr Lee has plans for expansion. Two years ago, his newest generation of breeding crocodiles came of age, allowing him to double his production of eggs.

He relies on the proceeds from his products, not from ticket sales or merchandising. He also does not import or export any live animals or eggs.

Mr Lee has three sons, aged eight, five and two. He says he will not force any of them to take over the business in the future.

“I want them to pursue their studies and take up other jobs if they like,” he says. “This is not something everyone can do. It’s a full-time commitment; a lifetime commitment.”

Singapore a top supplier of crocodile leather

Singapore is a major player in the international crocodile leather industry.

Long Kuan Hung Crocodile Farm exports 1,600 skins every year to places as far away as Europe and Japan.

While the numbers are small compared to what other farms around the world produce, some of the crocodile skin here will eventually be made into pricey, coveted handbags.

Another homegrown brand is Heng Long International, which is among the top five exotic skin tanneries in the world and has been supplying crocodile leather to luxury European fashion houses for decades.

The company, which has nearly 70 years of experience under its belt, processes more than a quarter of a million crocodile and alligator skins yearly.

Heng Long's executive director, Mr Koh Choon Heong, told The Straits Times last month: "Few Singaporeans realise that if they own a crocodile skin bag, it was most likely dyed in their very own backyard."

In 2011, the tannery was bought over by French luxury goods powerhouse LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton S.A. in a deal worth $161 million.

The Koh family reinvested a portion of the proceeds to maintain a 49 per cent stake in the company, with LVMH owning the remaining 51 per cent.

Heng Long supplies crocodile leather to other luxury brands also, including local brand Kwanpen.

Kwanpen traces its roots to its current president's father, Mr Kwan Pen, a first-generation Chinese immigrant to Singapore, who produced his first handmade crocodile leather bag in 1938.

Now headed by Mr Leonard Kwan, it has established itself as a reputable crocodile skin goods brand. Most of its skins are sourced from Heng Long.

Get The New Paper on your phone with the free TNP app. Download from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store now